In one of those conversations a person made a comment about how some Baby Boomers don’t understand technology, and while it turned out to be a bit tongue-in-cheek (the person followed up by speculating that the person being clueless was actually a ghost from the 18th Century misunderstanding modern copyright law). Anyway, it reminded my that I keep meaning to follow up on the post I wrote three years ago about the cavalier way some people use terms such as “Baby Boomer” and “Millenial.”

Some folks want to list anyone who is over the age of, say, 35, as a Baby Boomer. I’m seen just as many older folks insist that everyone under 30 is a Millenial. Which makes any commentary about the social and economic issues faced by people who grew up in different time periods meaningless.

The term Baby Boom originally referred to the significant uptick in the birth rate when World War II came to an end and when the world economy recovered from the Great Depression. Contrary to over-simplified understandings of history, those two events weren’t the same—the U.S. domestic economy was noticeably improving before the U.S. even entered the war, and the birthrate started picking up during the war itself (though not as dramatically as it did a few years later). So some sociologist and economists tagged the beggining of the Baby Boom in 1945, while others in 1942 or ’43.

Similarly, the birthrate’s rate of increase started slowing down in the U.S. (though not dropping) in the mid-fifties. Later, when social scientists started talking about the Baby Boom generation, many of them placed much importance upon the attitudes and expectations of that cohort based on their formative years being in the 1950s, where, in the U.S. at least, there was an exuberant economic boom and no war. I was in my late teens when I first started reading articles about the Baby Boom generation, and those articles defined is as people born between about 1942 and 1955. Which meant that my mother and father were both Baby Boomers.

Which is one of the reasons I sometimes have a negative visceral reaction to the more current definition, which is people born between 1946 and 1965. Because that makes me a Baby Boomer… and because I spent years thinking of my parents as Baby Boomers and that just seems wrong. Also, I was born after the 50s ended, and by the time my formative years were going, the U.S. was at war in Viet Nam and the Civil Rights movement was causing many to feel that the world was changing for the worse. So I think my assumptions about life are a bit different than those who grew up in the 50s.

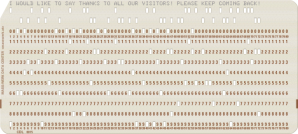

The chart that I reproduce above shows only one of the many possible definitions of generational groups. I believe for broad discussions about economics, sociology, politics, and the like that it is useful to make some generalizations about the broad societal conditions that people of different ages grew up under. A lot of people of my mother’s generation (The Silent Generation, people born between 1925 and 1945) supposedly don’t understand computers and modern technology. My mom has very strong feelings about several parts of Quantum Mechanics (word to the wise: if you don’t want to find yourself cowering in a corner, saying you are sorry and will never stray again, do not mention Erwin Schrödinger or his thought experiment about a cat and an atomic trigger within earshot of my mom, okay?). Once, when her computer had been misbehav ing for several months she told me that the reason she hadn’t called me was because none of the errors had risen to the level fo “kernal panic” and she had been able to get everything working again on her own.

Let me repeat that: my 76-year-old mother knows what a kernel panic is and is able to solve a lot of her computer and related problems on her own. So, just because they are a member of the generation before the Baby Boomers doesn’t mean they don’t understand technology.

And no one should be surprised that most of Generation X (whose original name was Gen X Atari Wave) understands technology, but I’ve noticed that a lot of member of both Gen Y (the original Millenials) and Gen Z don’t really understand how the technology works. They both understand many of the implications of the internet, but to varying degrees, they don’t understand how those things actually work, because it’s no longer necessary to understand things happening below the Presentation layer to use the technology. This isn’t a bad thing, per se. Just as you don’t need to know how to machine a piston in order to operate a car, you don’t need to understand all of that other stuff in order to be active on social media.

Unfortunately, that means that you have situations such as the one that started one of the comment threads I mentioned above: folks who don’t understand what a hyperlink on a web page actually is, will get upset and file a DCMA take down notice on someone who is linking to someone else’s publicly accessible page. But a hyperlink isn’t content, it’s a pointer.

For much of my life, the cliche was that older people didn’t know how to work new technological devices, and that the answer was to find a child who could fix things for you. Some of those “children”—the leading edge of Gen X—are 50 years old now. And some are now shaking their heads looking at the younger people who are much better at knowing how to make things go viral, for instance, but may not even know what HTML is.

* “All generalizations are dangerous, even this one.” ― Alexandre Dumas-fils

1 thought on “All generalizations are dangerous* — especially about generations!”